Burnt Yard Waste Becomes Sustainable Energy Storage

What if we could turn our yard waste into electricity? That’s just one of the questions Lamar Glover, a physics and electrical engineering professor at CSUDH, is exploring with students in his lab.

For centuries, biochar—charcoal produced from burning organic waste—has been used in soil remediation to improve water retention and boost nutrients. Glover and his students are looking at broader applications like renewable energy and energy storage. Already, they’ve used biochar to build capacitors that can power lights or other small devices.

“My research is focused on accessibility,” Glover said. “I don’t have a lithium mine in my backyard, but I do have a bunch of trees and other biomass.”

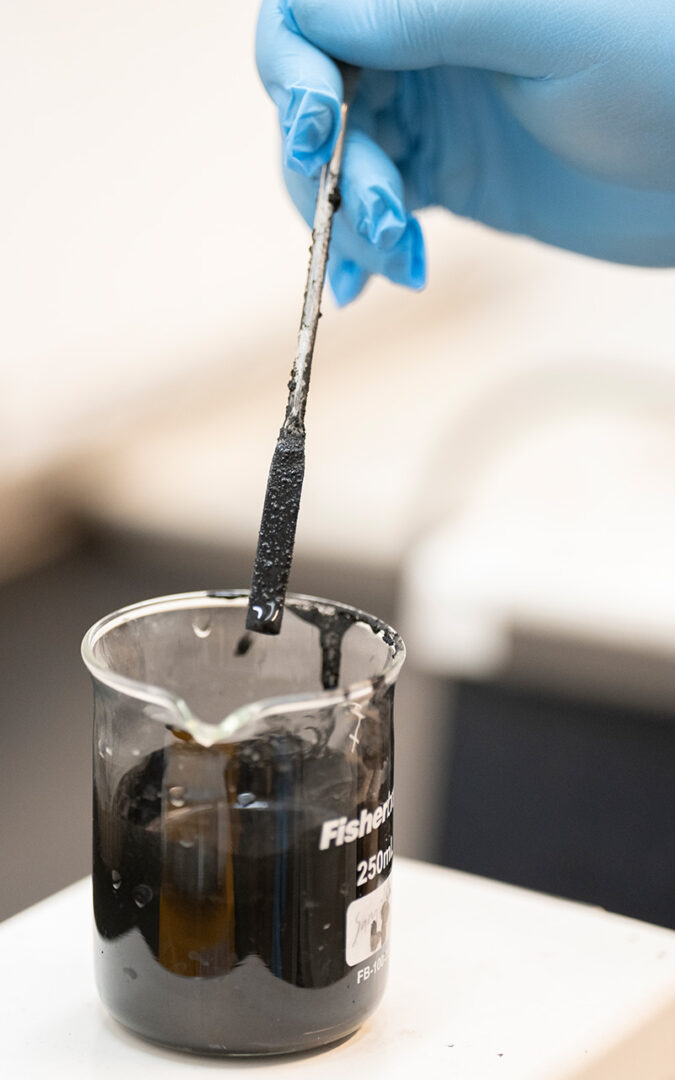

Glover produces biochar in a kiln purchased at Costco. After it’s burned, the biochar is ground into a fine powder and washed with water and vinegar to remove impurities and balance its pH.

Then, Glover and his students create a slurry of carbon, water, and polyvinyl acetate (or common white glue for the uninitiated). The slurry forms an adhesive ink and is applied to capacitors arranged on plates. After adding a separator and a little acid in the form of vinegar, the whole thing is closed up with a food vacuum sealer.

“We’re not making bleeding-edge technology here,” says Glover. “That’s really the point. We use things that anyone can buy at a big-box store.”

Glover mostly self-funded his research until late last year, when he secured a grant from the Baldwin Hills and Urban Watershed Conservancy to help promote and expand his research, which aims to use biochar to create more sustainable and less toxic forms of renewable energy.

Ultimately, Glover says he hopes to produce a usable prototype for a biochar-based device that could power a small streetlight or serve as a phone charger in public spaces like community gardens.

“It’s fascinating to teach people that physics and electrical engineering can be totally accessible to anyone, and you’re already halfway there by making biochar.”