Money Changes Everything

How NIL Payments are Transforming College Athletics

by Nick Bulum

After a breakout sophomore season at CSUDH last year, Toro basketball star Jeremy Dent-Smith had a lot of coaches and recruiters from larger Division I schools after him. (See related story) They offered the usual enticements that have been prying stars away from smaller programs for decades—bigger crowds, better facilities, televised games.

But they also offered something new: money. That’s because recent changes in National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) rules, and laws now on the books in states across the nation, allow colleges and universities to pay players. Or rather, they can offer “opportunities” for student-athletes to earn money. These opportunities are often coordinated by entities not directly affiliated with the schools and subject to little, if any, scrutiny or transparency.

After just a few years, this new, loosely regulated system allowing payments to student-athletes has upended college sports. Millions of dollars now change hands every year as Division I schools compete to lure the best players to their campuses. Established college stars can earn huge checks for appearing in TV ads or Instagram posts, something that was unthinkable even a decade ago.

And it all started with a video game.

Upon its debut in 1998, NCAA March Madness became a smash hit. The EA Sports line of video games, published by Electronic Arts, sold heavily throughout the 1990s and 2000s, and a key reason for that success was that the games closely duplicated the gameplay—and the real-life players—of sports from football to golf.

Whether it was Michael Jordan in NBA Live or Tom Brady in Madden NFL, gamers loved to play as their favorite athletes. For most of these games, Electronic Arts paid players for the right to use their name, image, and likeness (NIL). For professional athletes, buying those rights was simply a matter of signing on the dotted line and offering payment.

Two games in the EA Sports line-up were different, though. NCAA March Madness and NCAA Football depicted teams and players from colleges and universities—where NCAA rules forbid paying players from using their status as athletes for monetary gain. Instead, EA Sports paid the NCAA and universities for the rights to logos, uniform designs, and fight songs—while creating video game rosters made up of “fake” players who looked and played like their real-life counterparts. The actual college athletes depicted in the games were paid nothing.

This system existed for years—until former UCLA basketball star Ed O’Bannon saw a version of NCAA March Madness that featured the 1995 National Championship-winning squad he had played on.

O’Bannon noticed the team’s best player looked just like him: the bald head, the number 31 jersey, even the signature left-handed shot. To anyone who played the video game, it was obvious the digital player was supposed to be O’Bannon—even if the game called him by a different name. The rest of his UCLA teammates were also represented by virtual duplicates.

“I thought it was strange EA or the NCAA hadn’t contacted my teammates or me,” O’Bannon told the New York Times. “I’m not a lawyer, but something seemed off about that.”

Although an 11-year NBA career had left O’Bannon with plenty of money, he decided to pursue the issue in order to get justice for players who hadn’t been as talented or fortunate.

“I knew something had to be done,” O’Bannon said. “Most of my teammates never earned a dime from playing basketball, but there they were in this video game, selling for $60, while the NCAA gets paid.”

The 2009 lawsuit, O’Bannon v. NCAA, challenged the organization’s use of images and the likenesses of student-athletes for commercial purposes, and its rules preventing student-athletes from receiving any financial compensation other than college scholarships. Soon, other former stars like Oscar Robertson and Bill Russell added their names to the class-action suit. The NCAA, for its part, continued to insist that paying its athletes would be a violation of “the concept of amateurism” in sports.

U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken was largely unmoved by the NCAA’s arguments. In 2014, she ruled that barring payments to athletes amounted to an unreasonable restraint of trade and violated antitrust laws. The ruling set off a chain reaction, as other legal challenges and newly proposed state laws backed the rights of student-athletes to get paid.

California led the way in 2019, with the Fair Pay to Play Act, authored by State Senators Nancy Skinner and Steven Bradford (a CSUDH alumnus). The bill made California colleges and universities the first in the nation to allow student-athletes to enter into financial endorsement deals and hire agents. Similar laws in other states followed, and in 2021 the NCAA enacted a policy allowing NIL payments across all U.S. college sports.

“Most of my teammates never earned a dime from playing basketball, but there they were in this video game selling for $60, while the NCAA gets paid.”

An Uncertain Landscape

As the new landscape of paying college athletes takes shape, a new batch of entities has appeared on the scene. Called “NIL Collectives,” these organizations serve as clearinghouses for endorsement opportunities, matching student-athletes with businesses or individuals willing to pay them for various services, jobs, or appearances.

At Division I universities with huge sports programs and reputations, these NIL collectives have become de facto slush funds that supporters and boosters can pump unlimited cash into, with no requirements on reporting where it came from or who it’s going to. For example, in 2024, a pair of University of Kentucky basketball boosters contributed $4 million to the school’s NIL collective. Players can now receive hundreds of thousands of dollars for working at a Kentucky basketball camp, for instance.

“There’s no rules, no guidance, no nothing. It’s out of control. It’s not sustainable … The kids are going to be the ones who suffer in the end.”

Clemson University football coach Dabo Swinney to ESPN

In reality, there is nothing stopping a university’s NIL collective from paying student-athletes millions of dollars on the flimsiest of pretexts. Are a series of Instagram posts from a college football player really worth $200,000? Or is this just the latest iteration of the under-the-table payments that have long plagued college sports—now with a veneer of legality?

While the new system seems to have left behind the days of athletes getting stacks of illicit cash FedEx’d to them, it has opened up a Pandora’s Box of sorts. There is so much money at stake—and so much confusion as to how best to spend and regulate it—that no one seems quite sure what the end result of this process will be.

No Clarity on Rules

As they currently stand, NIL regulations vary from state to state and from conference to conference. Even schools within the same conference are approaching NIL opportunities in completely different ways. There are no universal rules on transparency or oversight, so most NIL offers are made outside of the public eye.

New lawsuits seem to emerge every week, challenging some aspect of the NIL landscape. Rules are in flux as administrators wait for the next court ruling to upend the system. Schools and athletic programs find themselves buffeted by constant rule changes even as they try to navigate the existing ones.

In this environment, most college athletics administrators are reluctant to talk about their NIL arrangements. During the writing of this article, the author contacted dozens of athletic directors and other university administrators involved in various aspects of NIL. Not a single major college athletics program agreed to speak on the record about NIL.

The same reticence emerged among mid-major institutions along the west coast. University of California, Irvine (UCI) Athletic Director Paula Smith was the only AD who would agree to speak on the record about NIL issues. She says at schools like UCI, the athletic department limits its role to providing relevant communication to potential sponsors and educating student-athletes on how the system works.

“We have several platforms where student-athletes can educate themselves about deals, opportunities, tax liability, and financial management,” says Smith. “We try to give them a base of information before they enter into any name, image, and likeness deal.”

The main way that UCI facilitates NIL opportunities for its student-athletes is through the creation of an online platform where sponsors can share opportunities to endorse products or services that students can consider.

“We communicate to all our student-athletes, ‘Here’s a marketplace. You can go on the platform, see what you’re interested in and what’s available and match a connection there,’ ” Smith says.

Smith says that NIL opportunities for UCI athletes mostly take the form of appearance fees for autograph sessions, payments for social media mentions, and similar offers. Most of these pay a few hundred dollars to student-athletes who agree to them.

Whoever wants to pay the most money, raise the most money, buy the most players is going to have the best opportunity to win. I don’t think that’s the spirit of college athletics.”

Former University of Alabama football coach Nick Saban at roundtable discussion hosted by Sen. Ted Cruz (R-Texas)

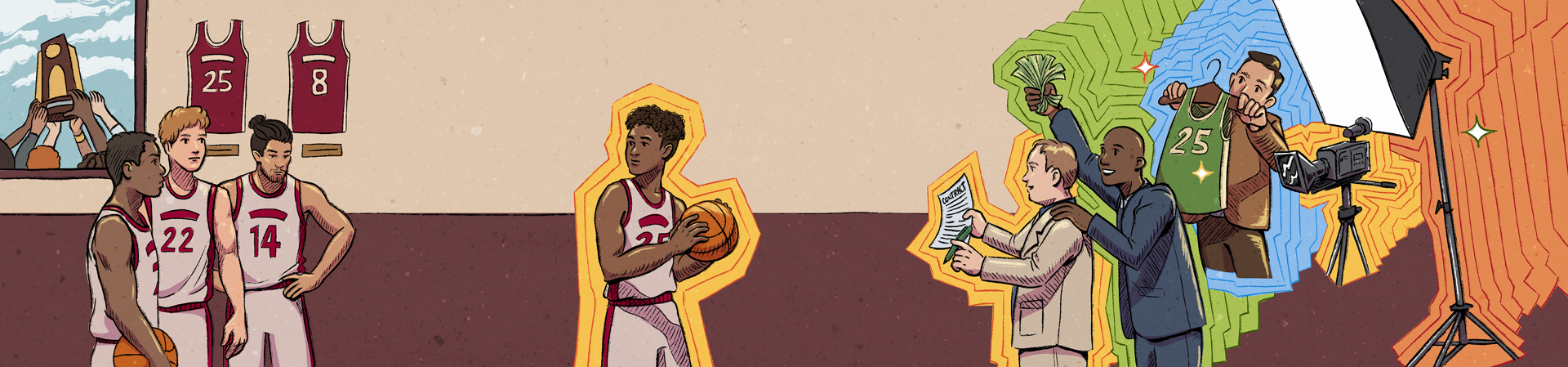

This stands in stark contrast to what is going on at schools in the so-called Power Four conferences—the Southeastern Conference (SEC), Atlantic Coast Conference (ACC), Big 10, and Big 12. Athletes at these schools are making many times what their counterparts at smaller schools have access to.

For example, Nick Saban, former head coach of the dominant University of Alabama football program, told ESPN that NIL costs there approached $13 million during the 2024 season alone. At the University of North Carolina, recent graduate Armando Bacot told the Run Your Race podcast that he earned more than $2 million during his stint with the Tar Heels basketball team—a number in line with what many of his teammates made.

Individual stars have certainly been able to cash in. University of Connecticut basketball star Paige Bueckers signed a lucrative deal with Nike. She became the first college athlete to have a signature shoe line released under her name. Similarly, University of Southern California hooper JuJu Watkins signed a deal to represent State Farm Insurance in a series of television ads.

Is this just a case of the rich getting richer, though? “I don’t know anyone who’s really benefiting outside the Power Four conferences,” says CSUDH men’s soccer head coach Eddie Soto.

The Transfer Portal Opens

Another recent rule change has exacerbated the situation. Previously, the NCAA required student-athletes transferring from one university to another to sit out one year and lose that year of eligibility. This discouraged most top athletes from transferring.

But that changed in 2021, when the NCAA began allowing transfer students to play immediately upon enrolling at a new school. The result is a system where student-athletes can switch schools more frequently—every year if they want to. Combine that with the money now available to student-athletes, and you’ve got a system ripe for chaos.

“It’s pretty wild right now,” says Soto. In his opinion, the changes to the transfer portal have made more of an impact than NIL money so far. Since top programs can recruit players from other college teams, Soto says the transfer portal hurts freshman athletes the most.

“There’s a win-now mentality in college sports that encourages coaches to find an established player who can come in and make an impact right away, rather than take a risk on an athlete coming straight out of high school,” he says. “With or without NIL money, I don’t see that changing any time soon.”

Now we can do legally what schools had been doing illegally. It’s like free agency…It’s going to become a bidding war… The landscape has really changed.”

Florida State University basketball coach Leonard Hamilton to Tennessee Democrat

NIL’s Impact on Division II

While most NIL legislation has been directed primarily at Division I programs and student-athletes, Division II programs like those at CSUDH are preparing for impact.

“It hasn’t really hit the Division II level yet,” says CSUDH men’s basketball coach Steve Becker. “We don’t deal with a ton of it. NIL really hasn’t impacted things drastically at our level yet, but I do think it’s coming.”

Fresno Pacific University Athletic Director Kyle Ferguson says some of his students got free gear or protein drinks in exchange for doing social media posts as a form of endorsement. “The negative side is we have lost a couple players,” he says, including their leading scorer in men’s basketball. “From what I was told, part of that had to do with the financial compensation that he was able to get elsewhere, which we just can’t give.”

That points to what has historically been one of the biggest threats to Division II athletics programs—larger, wealthier Division I schools poaching players who have outstanding seasons. These schools have long been offering perks to transfer athletes like better facilities and television exposure—but now they can add money to the mix.

“Team continuity is crucial in a sport like basketball, where success depends on playing as a team,” says Ferguson. “Our coaches have expressed how tough it is to build their teams the way they would like. Honestly, I’m not sure if maintaining that level of continuity is even possible anymore.”

There’s a lot of unrest because we all feel like there’s no rules—or the rules that are there are not being enforced.”

Ohio State University football coach Ryan Day to Bleacher Report

The Future of NIL?

Toros basketball coach Becker says regulations are needed to keep the NIL-transfer situation from worsening the sports experience and predicts that will happen soon. “It’s all wide open right now,” he says.

Fresno Pacific’s Ferguson isn’t willing to make any predictions about the future. “Where this all ends up in the next five to ten years is going to be super interesting to watch.”

“None of us at Division II schools are making a million dollars. We’re here to win games and, more importantly, to guide students toward earning their degrees.”

For his part, Soto sees the future as an extension of what’s already going on, just with more money at play.

“If a kid has a good season, they’re going to move on,” he says. “It’s just going to happen more and more because of the NCAA rules. The days of retaining these student-athletes are gone. It’s tough, and I think you’re seeing that across Division I and Division II programs, and across both successful and unsuccessful programs.

“It’s the wild, wild west right now. Everybody’s just doing their own thing.”