Unearthing

Ancient Mysteries

An unexpected discovery in northern Yucatán suggests permanent settlements are much older than previously thought.

Excitement mounted among the four anthropology students as their plane touched down in Mérida, near the northern tip of Mexico’s Yucatán peninsula. After multiple flights, their destination lay another two hours south in Oxcutzcab, a small agricultural town popular with visitors to the ancient Maya ruins that are scattered across hundreds of kilometers in the Puuc region.

Diana Chavez, a junior, and three fellow CSUDH students would spend four weeks working alongside local excavators to shed greater light on the history of the Yucatec Maya. Their focus? The history of these ancient settlements in an area of the country without access to any natural water supplies—except whatever rainfall the inhabitants could gather and store during the six-month wet season.

Chavez grew up watching Indiana Jones swashbuckle his way across the remains of multiple civilizations, which taught her that archaeology is a valuable pursuit—minus the bullwhip and exploitation. “I’m interested in a more ethical approach,” she says, “that balances museum curatorship with the need for repatriation of artifacts to the cultures that produced them.” She credits two other influences for her interest in archaeology: her father and his love of history; and Ken Seligson, an archaeological anthropologist and associate professor at CSUDH, whose passion for Mesoamerican history helped convince her to transfer from Long Beach City College.

Seligson began the field work program in 2019, so that CSUDH students could participate in valuable field experience and help direct their professional interests. The goal for this trip was to conduct a series of test excavations in the Kaxil Kiuic Biocultural Reserve; specifically, an ancient platform and ball court dating to somewhere between 900 BC and 300 BC.

The students and professor set out to focus their research on the timeline of the settlement at two sites: Cerro Hul and Xanub Chak. But that took a back seat after Seligson’s students, working alongside Yucatec Maya excavators, made an extraordinary discovery that could fundamentally alter the chronology of how and when Maya civilization took root in the Puuc region.

A Groundbreaking Find

Mexican law requires local workers be hired for excavation at archaeological sites. The policy aligns with Chavez’s thoughts about the questionable ethics of Hollywood explorers: that the people whose history is being studied should be the ones directly in contact with their land. After the indigenous excavators remove dirt and debris from the dig site, they hand off what has been uncovered to archaeologists like Seligson and his students, who can then clean up and study what they found. So it was José Chi Xool, one of the Yucatec Maya working with the student team, who first uncovered the surprising artifact, buried beneath centuries of dirt.

Alyssa Guerrero, a senior, says the day of the discovery started like any other. The team was less than a week into their field work, hiking two sweaty kilometers each day through newly cleared jungle track to get to the site. They gathered near the platform dig site at Xanub Chak, as José Chi Xool uncovered pieces of a centuries-old plate—already a valuable find. “And then we heard him say, in Spanish, ‘That looks like a doll.’ ”

Doll or figurine, nothing like it had ever been unearthed this far north. Seligson says similar artifacts were being made in northern Guatemala and western Belize, but archaeologists haven’t discovered any in this region of Mexico. He and the students knew immediately that they had stumbled on an artifact of particular importance. “It’s the coolest thing I’ve ever found in my 14 years of working here, and the students managed to find it on their fourth day of excavation,” Seligson says. “We don’t know for sure yet what to make of it.”

For Guerrero, the moment recalled what CSUDH Professor Jerry Moore said in his ancient civilizations course. Specifically, that the practice of archaeology often amounted to long periods of boredom punctuated by brief moments of excitement. “Fortunately, we didn’t have to wait that long for the exciting stuff,” Guerrero says.

Uncovering the Maya World

Seligson says the discovery of the figurine was a delightful surprise. “We weren’t there to find artifacts like that. We were there to look at a specific iteration of sociopolitical evolution in the region.”

Since 2010, Seligson has spent four weeks each summer in the Puuc region to examine the chronology of permanent settlement and how the communities that lived there related to larger and better-known Maya centers further south. The 4,500-acre Kaxil Kiuic Reserve, where this dig site is located, is owned by a nonprofit formed at Millsaps College in Mississippi. Millsaps also operates a research lab and guest houses 30 minutes away, where Seligson and his students gained temporary respite from the sweltering summer heat.

Since its establishment, the Kaxil Kiuic Reserve has provided archaeologists with intriguing new details about the ancient Maya communities that once lived in the Puuc region, despite its challenging geology and geography. “There is no surface water at all,” Seligson says. “No streams, no lakes, no rivers, nothing—and it only rains for six months out of the year.”

Permanent settlement required careful resource management systems. To survive, people living there had to develop intricate environmental mechanisms, Seligson says—for example, capturing and storing enough water to last through the long dry season.

Archaeologists have long thought that settlers in the Puuc region arrived in the late Preclassic period from about 300 BC onward. Tomás Gallareta Negrón, a senior archaeologist with Mexico’s National Institute for Anthropology and History, says that recent archaeological evidence suggests a much earlier date.

“We know from the arrangement and type of buildings that we’re finding that these communities were much larger and more sophisticated than we once thought,” says Negrón, who has worked at such important Maya sites as Cobá, Uxmal, Chichen Itzá, and Isla Cerritos. “We also know that they arrived much earlier than previously thought, probably around 900-1000 BCE.”

The discovery of the figurine suggests that Puuc Maya communities had ties with larger cultural centers to the south. “The discovery of the figurine pushes back on the idea that the region was a cultural backwater until the South started to collapse and people moved North,” Seligson says. “It tells us that there was a parallel cultural trajectory in the North.”

Tools of the Trade

Jose Quintero, a senior anthropology major with a concentration in archaeology, says getting such valuable field work experience brought the Puuc Maya community to life. “Classroom archaeology is one thing, but I’m learning that archaeologists want to be out in the world and doing archaeology,” he says.

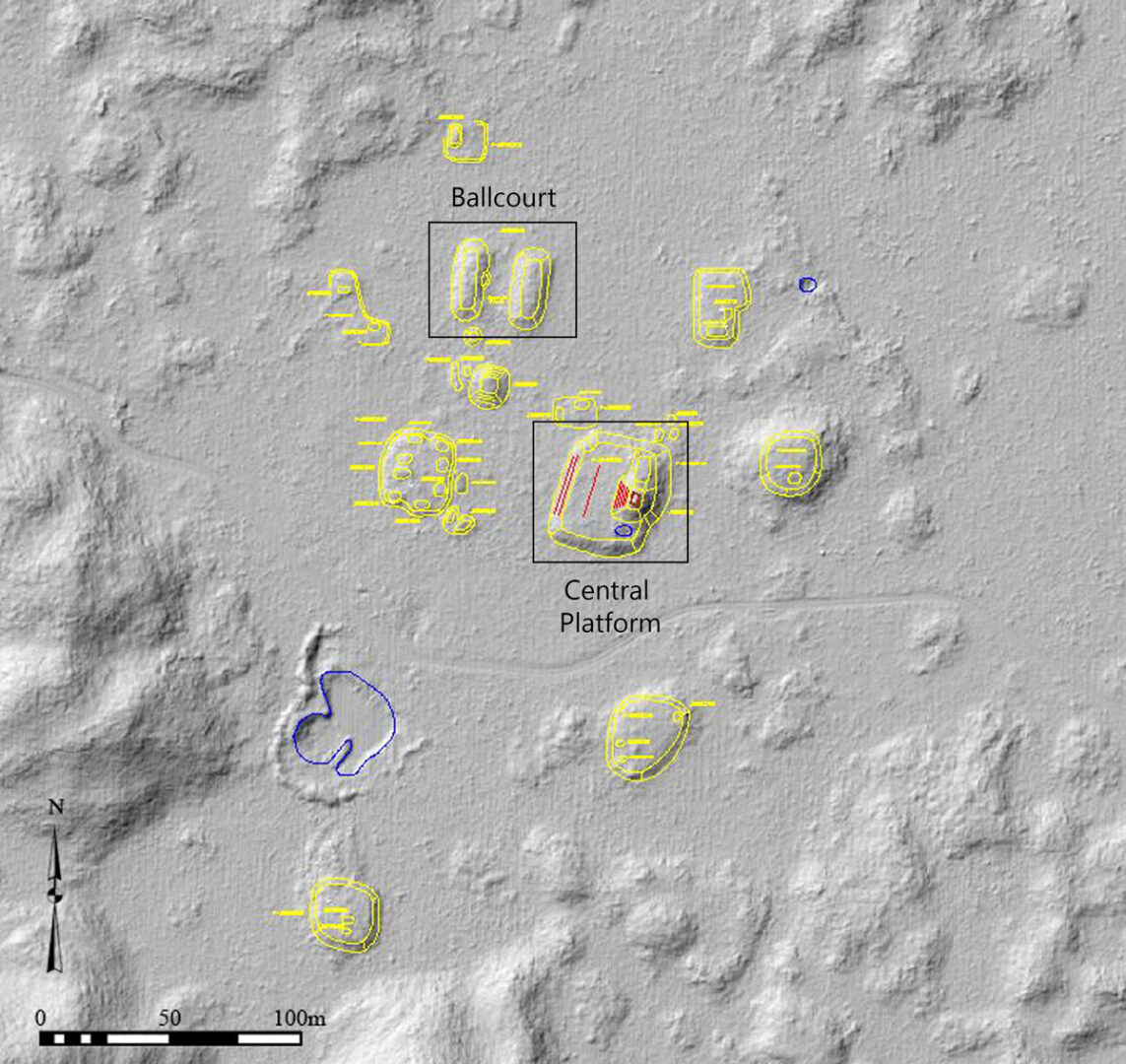

Quintero worked with Seligson to create LiDAR mapping of the areas the team wanted to explore during this field work season. He also used GPS readings to measure and orient the outlines of structures revealed by LiDAR. “You really get the sense that you’re sort of seeing what the people who lived here thousands of years ago saw,” he says.

Reese Santonil came to archaeology by way of computer science. The senior anthropology major spent part of the field work season creating 3D renderings of artifacts excavated and catalogued in the Kaxil Kiuic Reserve, including some of the new ceramic fragments the CSUDH team uncovered.

The process involves setting the artifact on a white backdrop and photographing it from all different angles. “To get the finished rendering, I use software that stitches the images together to create a 3D model,” Santonil says. The images can be used to create a virtual catalogue that students and other researchers around the world can access when they can’t visit Kaxil Kiuic in person.

Chavez is pursuing an individual research project, called Star Sanctuaries and Platforms, which looks at the spatial orientation of Ma-ya structures and whether that might correlate to religious or ritual use. The project combines archaeology, culture, and religion, and Chavez drew inspiration from her Honduran grandmother—a curandero, or traditional healer. “She was very syncretic about religion, combining traditional Catholic elements with older folk traditions. That really prompted my interest in cultural anthropology.”

Past and Present

Seligson hopes the field work experience gives his students a broader perspective on the people that lived in the Puuc region thousands of years ago, and the ones that still do. “One of the things driving my own research is the need to help people understand that the Maya culture overall is not a culture of the past,” he says. “There are still seven million Maya people alive and well today.”

There’s still a lot about the Puuc Maya that remains unknown, says Seligson. “It’s like working on a jigsaw puzzle without having the cover of the box to know if you’ve got it right.” He says the 2024 field work season will focus on broader excavations at the Xanub Chak site where the figurine was discovered, and supported by a new three-year grant from the National Science Foundation.

“We’ve clearly confirmed that the site is Middle Preclassic, dating from between 900 BCE and 350 BCE,” says Seligson. “Now, we want to learn more about the construction history of some of the buildings. Why did the people in this community not build on top of the platform and ball courts when they did so at other sites from the same period?”

A lot more work remains to be done, says Seligson, who plans to publish a paper this year with his students on the discovery of the figurine. “We have a lot of broader questions we want answers to, and that will require a lot more excavation. We’re really just at the start of it.”

Enlightening LiDAR

Light Detection and Ranging, or LiDAR, is a remote sensing method that uses a pulsed laser to map the contours of the Earth’s surface. Data is gathered by an instrument attached to a low-flying aircraft that emits 150,000 laser pulses every second.

LiDAR helps researchers see beneath the thick canopy. Just like sunlight through leaves, a few laser pulses reach the ground every square foot. Maps can then be generated by digitally removing the forest canopy to reveal the contours of physical structures on the ground beneath.

This technology saves time and is much less invasive than older practices says Seligson. “For an area the size of two kilometers, it could take as many as five or 10 years of walking back and forth on the forest floor to gather enough data for a map. It would also require cutting back a lot of the forest.”